The Cowley CourierTraveler

April 7, 2017

Kansas House formally recognizes Etzanoa

By FOSS FARRAR

Etzanoa Conservancy

TOPEKA — The Kansas House of Representatives on Wednesday recognized recent archaeological research pointing to Arkansas City as the site of the huge ancestral Wichita settlement of Etzanoa.

House members applauded after approving a resolution that was read by Anita Judd-Jenkins, Republican representative from Ark City.

Standing behind her as she read from a podium were several Ark City residents, archaeologists and archaeology enthusiasts who have promoted and participated in the studies of the prehistoric Native American site.

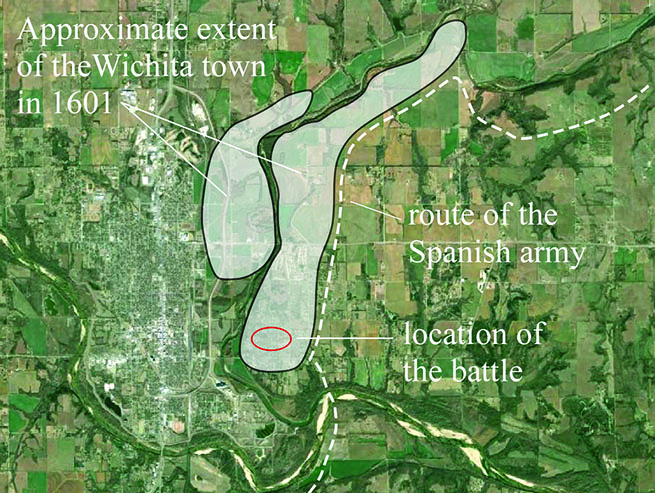

“Based on the evidence, the Etzanoa archaeological site of a 5-mile-long settlement of an estimated 20,000 ancestors of the Wichita tribe, thrived from about 1425 to the early 1700s,” Judd-Jenkins said in prepared remarks.

“Archaeologists agree that a city of this size would be the second-largest prehistoric Native American site ever discovered in the U.S. and Canada, making it a possible candidate for being designated as both a World Heritage Site by UNESCO and a National Historic Landmark.”

Judd-Jenkins noted that Spanish explorers in 1601 followed up on a previous search for Quivira, the land of the “lost cities of gold.” Francisco Vazquez de Coronado led an earlier expedition to central Kansas in the early 1540s.

In 1601, Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate, the first governor of New Mexico, led 130 men on the trek north and east from New Mexico into Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. Oñate and his men eventually reached a town near the confluence of two rivers that they called the “Great Settlement.” The natives called the town “Etzanoa.”

The Spaniards documented the visit to Etzanoa, including their observations and measurements of the town and their estimate of its population. Their observations were recorded a year later in Mexico City. A large volume comprising those documents includes two expedition maps. It is now preserved in Seville, Spain.

Judd-Jenkins introduced the following people who traveled to Topeka to witness her presentation:

Don Blakeslee, Wichita State University professor of archaeology; Robert Hoard, State Archaeologist of the Kansas Historical Society; Otis Morrow, V.J. Wilkins Foundation trustee; Karen Zeller, V.J. Wilkins Foundation trustee; Nick Hernandez, city manager of Arkansas City; and Jay Warren, city commissioner and former mayor of Arkansas City.

Hap Mcleod, Etzanoa Conservancy president; Adam Ziegler, Lawrence Free State High School student and discoverer of the first Spanish artifact at the Etzanoa battle site; and the following Etzanoa Conservancy members — Jann Ziegler, who is Adam’s grandmother; Carol House, archaeological site land owner; Jason Smith; and Foss Farrar.

In her presentation, Judd-Jenkins said citizens of Ark City have long known that the area near the confluence of the Arkansas and Walnut Rivers in eastern Arkansas City was someplace special. In 1870s, early Ark City residents found many Native American artifacts including broken pots, earth pits full of bones, rock carvings and tools.

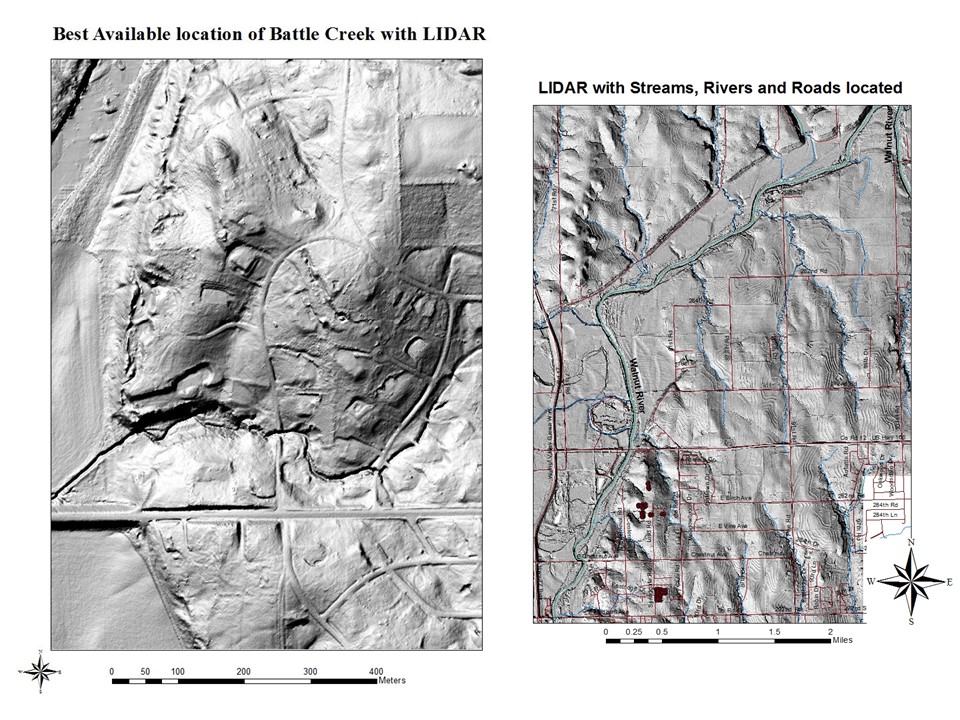

Judd-Jenkins summarized findings from recent field studies conducted along the banks of the lower Walnut River in eastern areas of Ark City.

Archaeological teams who surveyed eastern Ark City prior to the building of the U.S. 77 bypass found artifacts dating from 600 to 1800 AD, based on carbon dating, she said. And a large-scale field study in Ark City during the summer of 2015 using some of the latest archaeological technology turned up more artifacts, including metal balls fired in canister shots from canons during a battle at the southern end of Etzanoa.

WSU archaeologist Blakeslee organized and led the 2015 archaeological study. Blakeslee’s teams spent a week in surveying the Etzanoa site in Ark City and another week in Lyons doing follow-up studies of a Quivira site there. He and his teams used magnetometers and metal detectors as well as a mobile archaeological lab that tested potential artifacts.

“With the generous funding of the V.J. Wilkins Foundation, the Archaeology Channel spent two weeks filming the 2015 archaeological studies conducted by Dr. Blakeslee and his teams,” Judd-Jenkins said, “with the cooperation and support from the city of Arkansas City, and the Arkansas City Historical Society.”

Then she announced that the Archaeology Channel’s film, “Quivira: Conquistadors on the Plains,” was being shown continuously on Wednesday in the Statehouse Visitors Center Auditorium.

“It describes the work and discovery of the true Etzanoa on the banks of the Walnut River in south-central Kansas, just above the Oklahoma border,” she said.